in this blog

Skip the OCR: How Few-Shot Prompting Extracts Structured Data from PDFs at a Fraction of the Cost

When you need to extract data from PDFs, the default advice is straightforward: use an OCR service. Tools like Reducto, Amazon Textract, or Google Document AI promise pixel-perfect text extraction. But here's what nobody tells you: if your documents follow a consistent format, you're probably overengineering the solution.We recently built a document processing pipeline for technical product specification sheets: hundreds of PDF documents, each containing tables with measurements, configuration parameters, and equipment details. The instinct was to reach for a dedicated OCR service. Instead, we shipped a solution using PyPDF2 for basic text extraction and GPT-4o with few-shot prompting for structure. The result: structured JSON output, validated against Pydantic schemas, at roughly 10x lower cost.

The Problem with OCR-First Thinking

OCR services solve a hard problem: extracting text from scanned documents, handwritten notes, or complex layouts where the text layer is missing or unreliable. They're excellent when you need them.

But many real-world PDFs aren't scanned images. They're digitally-generated documents with embedded text layers. When you open them in a PDF reader and hit Ctrl+F, the search works. The text is already there.

For these documents, running OCR means:

- Paying per page for something PyPDF2 does for free

- Managing API integrations, rate limits, and authentication

- Adding latency to your pipeline

- Getting back raw text that still needs parsing into structured data

That last point is critical. Even with perfect OCR, you still need to transform unstructured text into usable data structures. The OCR step becomes pure overhead.

A Concrete Example

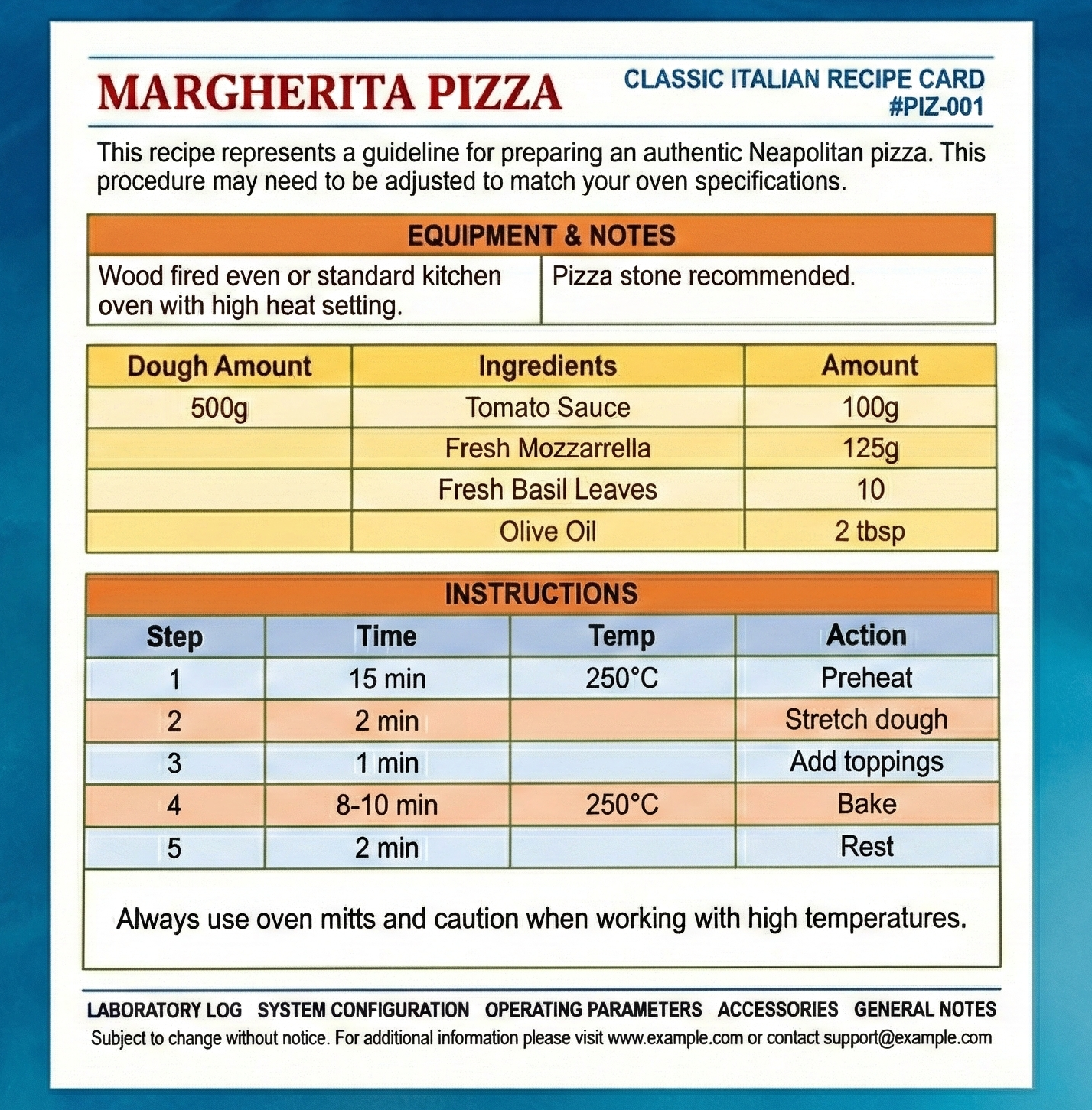

Let's look at a simple scenario: extracting data from recipe cards. Here's a typical document:

When we extract the text using PyPDF2, we get something like this:

ABORATORYLOGSYSTEMCONFIGURATIONOPERATINGPARAMETERSACCESSORIESGENERAL

NOTESSubject to change without notice.For additional information please

visit www.example.com or contact support@example.com

MARGHERITAPIZZACLASSIC ITALIAN RECIPE CARD #PIZ-001Thisreciperepresents

aguidelineforpreparinganauthenticNeapolitanpizza.Thisproceduremayneed

tobeadjustedtomatchyourovenspecifications.Woodfiredovenorstandard

kitchenovenwithhighheatsetting.Pizzastonerecommended.DoughAmount500g

Ingredients100gTomatoSauce125gFreshMozzarella10FreshBasilLeaves2tbsp

OliveOilStepTimeTemp1Preheat15min250°C2Stretchdough2min3Addtoppings

1min4Bake8-10min250°C5Rest2minAlwaysuseovenmittsandcautionwhen

workingwithhightemperatures.

Look at that. Words are fused together: `Thisreciperepresentsaguidelineforpreparinganauthenticneapolitanpizza`. Table data is concatenated: `100gTomatoSauce125gFreshMozzarella10FreshBasilLeaves`.

Section headers blend into content. This is what happens when PDF text extraction hits multi-column layouts: the reading order gets mangled.

Sure, an OCR service would give you clean, properly-spaced text. But you'd still need to parse that text into structured data. The key insight is that LLMs are remarkably good at understanding messy input. If the model can figure out the structure from jumbled text, why pay for a cleaning step you don't need?

Few-Shot Prompting as a Parsing Strategy

The alternative is to let an LLM handle the structure. With few-shot prompting, you provide examples of input-output pairs, teaching the model your exact schema without fine-tuning.

First, define what you want with Pydantic:

from pydantic import BaseModel

from typing import List, Union, Dict, Any

class Ingredient(BaseModel):

amount: str

item: str

class Step(BaseModel):

step: int

action: str

time: str

temperature: str

class Section(BaseModel):

section_title: str

content: Union[str, List[Ingredient], List[Step]]

class RecipeModel(BaseModel):

title: str

recipe_code: str

sections: List[Section]

This isn't a loose JSON blob, it's a typed contract. The schema enforces structure: ingredients must have amounts, steps need integer IDs, every recipe has a code.

Now, the few-shot examples teach the model how to handle the scrambled extraction:

EXAMPLE_RAW = """

MARGHERITAPIZZACLASSIC ITALIAN RECIPE CARD #PIZ-001Thisreciperepresents

aguidelineforpreparinganauthenticNeapolitanpizza.Woodfiredovenor

standardkitchenoven.Pizzastonerecommended.DoughAmount500gIngredients

100gTomatoSauce125gFreshMozzarella10FreshBasilLeaves2tbspOliveOil

StepTimeTemp1Preheat15min250°C2Stretchdough2min3Addtoppings1min

4Bake8-10min250°C5Rest2minAlwaysuseovenmitts.

"""

EXAMPLE_JSON = {

"title": "Margherita Pizza",

"recipe_code": "PIZ-001",

"sections": [

{

"section_title": "Summary",

"content": "This recipe represents a guideline for preparing an authentic Neapolitan pizza."

},

{

"section_title": "Equipment",

"content": "Wood fired oven or standard kitchen oven. Pizza stone recommended."

},

{

"section_title": "Ingredients",

"content": [

{"amount": "500g", "item": "Dough"},

{"amount": "100g", "item": "Tomato Sauce"},

{"amount": "125g", "item": "Fresh Mozzarella"},

{"amount": "10", "item": "Fresh Basil Leaves"},

{"amount": "2 tbsp", "item": "Olive Oil"}

]

},

{

"section_title": "Instructions",

"content": [

{"step": 1, "action": "Preheat", "time": "15 min", "temperature": "250°C"},

{"step": 2, "action": "Stretch dough", "time": "2 min", "temperature": null},

{"step": 3, "action": "Add toppings", "time": "1 min", "temperature": null},

{"step": 4, "action": "Bake", "time": "8-10 min", "temperature": "250°C"},

{"step": 5, "action": "Rest", "time": "2 min", "temperature": null}

]

},

{

"section_title": "Safety Notes",

"content": "Always use oven mitts."

}

]

}

Two or three examples are typically enough. The model learns to split fused words, recognize that `100gTomatoSauce125gFreshMozzarella` is actually two ingredients, and map section keywords to structured fields.

The Pipeline

Text extraction is trivial:

from PyPDF2 import PdfReader

def extract_full_text(pdf_path: str) -> str:

reader = PdfReader(pdf_path)

return "\n".join(page.extract_text() or '' for page in reader.pages)

The LLM chain combines the schema, few-shot examples, and raw text:

from langchain.output_parsers import PydanticOutputParser

from langchain_openai import ChatOpenAI

output_parser = PydanticOutputParser(pydantic_object=DocumentModel)

prompt = PromptTemplate(

template="""Convert this PDF text into structured JSON.

Schema: {json_schema}

Raw Text: {text}""",

input_variables=["text"],

partial_variables={"json_schema": output_parser.get_format_instructions()}

)

chain = LLMChain(llm=ChatOpenAI(model="gpt-4o", temperature=0), prompt=prompt)

The output parser enforces the Pydantic schema. If the model returns malformed JSON or missing fields, validation fails explicitly. Silent data corruption is not an option.

When This Approach Works

This pattern excels when:

1. Documents are digitally generated, and the text layer is easily extractable.

2. Formats are repetitive, so docs are slight variations of the same template.

3. You need structured output, and the goal is JSON, database records, or API payloads (not raw text).

4. Volume is moderate, hundreds or thousands of documents, not millions per day.

Our use case hit all four. Specification sheets from the same source follow identical layouts. Section headers are consistent. Tables have predictable columns. Two few-shot examples covered the entire document family.

The Cost Math

Modern OCR services like Reducto do support structured extraction with schemas, so the comparison isn't "OCR + separate parsing" vs "direct LLM parsing." It's simpler than that: you're paying for a capability you may not need.

Reducto charges around $0.01-0.05 per page depending on volume and features. That's reasonable, but it adds up. With PyPDF2 + GPT-4o, you're looking at roughly $2.50 per million input tokens. A single-page document with few-shot examples might use 2,000 tokens total. That's about $0.005 per document, and you get structured output directly.

For 500 documents: ~$2.50 with the LLM approach vs $5-25 with an OCR service. The gap matters more at scale, but the real win is simplicity. One fewer service to integrate, authenticate, and maintain.

Limitations

This isn't a universal solution. You still need OCR when:

- Documents are scanned images without text layers

- Layouts vary significantly between documents

- You're dealing with handwriting or degraded print quality

- The text extraction from standard libraries produces garbage

Test PyPDF2 (or pdfplumber, or pymupdf) on a sample document first. If the extracted text is somewhat readable (even if messy) few-shot prompting can handle the rest.

Conclusion

The document processing ecosystem has a bias toward powerful, general-purpose tools. But engineering is about matching solutions to problems. For repetitive, digitally-generated PDFs where you need structured output, few-shot prompting with validated schemas is faster to implement, cheaper to run, and eliminates an entire integration layer.

Start with the simplest extraction that could work. Reach for OCR when you actually need it.